Have you ever wondered why your friends are so different from each other, yet you all still share a set of common values? How about siblings embracing different character traits though they share much else with each other? Teams at work: ever noticed that from the outside other teams appear to have hired very similar individuals, while your team, within the scope of its responsibilities, still has a “diverse” set of individuals? What’s going on here?

The following is a conjecture: Groups maximise the variance within the bounds that define them. Each group has a set of inflexible criteria for participation. These define the boundaries, therefore in this sense, each group is bounded. Any member of that group must meet those criteria. Once met, each member of that group occupies unclaimed space, and as the group grows larger, the space is occupied with everyone taking a distinguishable, distant position from the rest of the members. Each member therefore contributes to maximising the variance within the defined bounds.

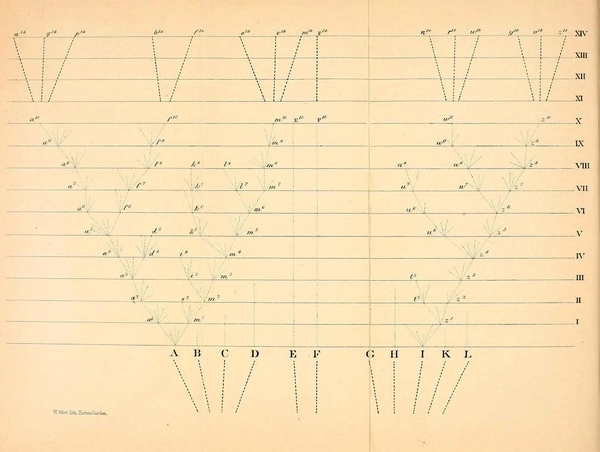

As much as I would have wished this was a novel insight, experience has taught me humility. The topic must have been studied at a more fundamental level by someone else and it turns out it has. That someone else is Charles Darwin, and this phenomenon, which he identified in the Origins of Species, is called the the Principle of Divergence.

The Principle of Divergence

In September 1857 in a letter [1] to Asa Gray, Darwin writes:

One other principle, which may be called the principle of divergence plays, I believe, an important part in the origin of species. The same spot will support more life if occupied by very diverse forms: we see this in the many generic forms in a square yard of turf (I have counted 20 species belonging to 18 genera), — or in the plants and insects, on any little uniform islet, belonging almost to as many genera and families as to species. … the varying offspring of each species will try (only few will succeed) to seize on as many and as diverse places in the economy of nature, as possible. Each new variety or species, when formed will generally take the places of and so exterminate its less well-fitted parent. This, I believe, to be the origin of the classification or arrangement of all organic beings at all times. These always seem to branch and sub-branch like a tree from a common trunk; the flourishing twigs destroying the less vigorous.

In other words, Darwin argued that Natural Selection [3] tends to favor species that face the least competition from other organisms. The role of divergence is to minimise such competition, thus increasing the likelihood of survival.

At the age of 22, Darwin joined the Beagle Expedition (1831 to 1836) [4] as a naturalist, and for thext 5 years he would meticulously record his observations. In 1859 he published his findings and research in the book On the Origins of Species [2:1], which has become the foundation of evolutionary biology. In 1829, 2 years prior to the Beagle Expedition, when 20 year old Darwin was still studying at Cambridge, he writes: “My studies consist in Adam Smith and Locke”[5].

It should not be a surprise that Darwin’s Theory of Natural Selection more generally and the Principle of Divergence more specifically rest on a fundamental concept: Competition. Coincidentally, it is also what got me thinking about group dynamics.

So, the maximising of bounded variance?

There’s no need for it. I think the concept is fully explained by the Principle of Diverge. The bounds are an attribute of the environment, much too similar to what defines groups (even the ones who exist online). The engine for maximising the variance within those bounds is competition. I can’t help but smile at the irony of such realisation with relation to some groups, particularly the altruistic kind.

Reading more on this topic has been a good reminder on two things: Ideas compound and some of the most interesting insights really do exist at the intersection of disciplines.

Darwin letter to Asa Gray, Sep 5th, 1857 ↩︎

On the Origin of Species e-book - Project Gutenberg ↩︎ ↩︎

Natural Selection - Wikipedia ↩︎

Second voyage of HMS Beagle - (1831 to 1836) ↩︎